#the fact that nero is the only commoner makes him even more special bc there's so much going on with him

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

everyone in team 9 is special you have chief of the twilight clan's daughter, scarlet witch's reincarnation, ruschia's next possible king, and nero pachelbel

#the fact that nero is the only commoner makes him even more special bc there's so much going on with him#even in the first chapters he's already someone special bc of his geniusness#PLEASE still be a commoner who just happen to have special eyes#and?? he said he had an opportunity to learn cutting edge from a different country and i assume that's frezier#so um hm *if* he is from heavenly empire then that's his birthplace(?) -> frezier where he learned a lot -> ruschia where he have fun mome#nts in life#lapis is eventually gonna go back to frezier makia have two choices it's to stay in lune or study in frezier#there's no reason for frey to leave ruschia unless the king's gonna send t#gonna send him to another country to study which. doubt? bc iirc one of his brothers is already in frezier?#nero.... will he even be safe in lune anymore who knows.. will he be allowed to stay#sylhea talks maydare

1 note

·

View note

Text

Air hiking and Vergil, an essay.

(with headcanon and canon evidence)

But no, like the fact that every fucking playable character has fucking air hike or at least some kind of their own version of it except Vergil is so fucking hilarious to me.

See we got the demons/demon hybrids that have the actual move air hike itself:

Dante

Nero (though I'd imagine it took him just a little while to get use to and it only did unlock when his arm awakened)

Trish

Lucia

Then we have the human(ish* in V's case) characters that have their own creative license to have their own version of the move:

Lady, who used the Kalina Ann to launch herself up further into the air.

V, who simply just uses Griffon to leap up and glide up in the air to go where he needs to go/get him out of a pinchful situation, he's fragile afterall.

Then there's Vergil

He can't double jump. He can't air hike. The closest thing he's got is his version of Trick, which can be very limited and very different compared to Dante's version of Trick, he can trick up but that's not going to get him very for if there's nothing for him to focus on (enemy to lock on to) so that makes Vergil completely miserable when it comes to platforming look at the entirety of dmc 3 SE at that, no longer Dante got to the top of the tower before he did it must have taken Vergil forever to platform his way up (I'm going to say the portal cutting wasn't a trick in Vergil's arsenal until after his time in hell, mostly bc its funnier that way to think about that way)

And since every demon/hybrid playable in the series has air hike I'm going to headcanon it's a very common skill for demons to learn when their younger. Like when they're tiny demonlings and their parents teach them how to hunt, protect territory and stuff, the basics that's like one of the very first things their taught.

So I'd like to imagine Sparda, very excited now the Eva has finally let go of the reigns a bit and is allowing Sparda to begin teaching the twins demon stuff, just launching baby Dante and Vergil up into the air and catching them over and over in hopes that inner demonic instinct will kick in to become airborne just a bit longer where their inner energy, what's at the center of their core and powers all their demonic flood and will be the same source of their future trigger,, will spark into that pentagramic shape underneath and give them that boost.

Dante picks it up also immediately, only with a few throws the baby is a giggling mess as the moment his father throws him up he only springs up himself higher than his father throws him in a flash of red sparks coming underneath him almost trampoline like.

Vergil, however, doesn't. It's odd, given future context with just how quickly Vergil picks up new things: look at how quickly he mastered Beowulf given the fact he only used it in one canonical fight and only gotten it not linger before that said fight. Or look how quickly he master his Sin devil trigger and his doppelgänger - both skills I'm very sure came to him post V's return or else we would've seen at least traces of them in earlier fights. But no matter how many times Sparda throws his eldest it just never clicks. Eva has to convince her husband to eventually stop because it's clear for some reason it isn't going to happen right now, maybe it'll come to him eventually later when he grows up more - but it never does. And maybe this is also like a motivated of sorts, even when he was younger, to learn everything else as best and with as much mastery as possible because of the fact his air hike skill never came to him.

I like to imagine air hiking is supposed to be something young demons are supposed to learn before they hit a certain age range (Nero I want to mention is a special case given how I general his power sprung late but even there air hike came natural to him after awhile) like how talking/some form of communication usually is for humans, afterall air hiking intended in nature(? Hell is this case) is a skill for avoiding/dodging/ in combat - survival - or used for moving and maneuvering around the demon world's vastly different landscapes. So it's kind of hard for a demon once they hit a certain age and they've somehow missed the learning period to learn such a skill and Vergil a man, even though in human years, is now in his mid 40's if he couldn't learn it when he was 19 he's surely going to have an impossible time learning it now.

However I don't think to him now it means as much, he has other alternative means and battle skills that can help him out to be extremely deadly without the skill - post dmc 3 - his version of Trick is more faster than it ever was, while Dante's Trick relies more on teleportation methods Vergil's works by nothing but pure speed.

Yes, his tick up/trick down/trick sides are nothing but him moving extremely, extremely fast. Have you ever wondered how the fuck his judgment cuts work? It's him just him moving so inhumanly fast you can't even see him move and actually cut into anything. One of Vergil's most key skills is: The. Fucker. Is. Fast. DMD Vergil in my eyes is the canon Vergil when it comes to his strength, how he fights, ect and the trick to fight Vergil ESPECIALLY in dmc 5 is overspeed the fucker before he outspeeds you; and he will, the moment you make one slip up or look away, fucking disintegrate your health bar before you even realize what the fuck happened.

The motivated fucker is overpowered, as a boss, as a playable character, we all know this. And I like to think in universe, the goddess of Time or whatever deity that oversees Vergil fucking KNEW and was like... "OK we need to nerf this bitch at least a little bit." Because imagine a universe if Vergil had air hike. Imagine. Literally there would be not a single fucking thing wrong with his play style, it would just be: push buttons to win.

Damage? What's that?

when I CAN FUCKING VERTICAL SLASH, TRICK UP, LUNAR PHASE, AND FUCKING AIRHIKE THEN REPEAT??? GROUND??? WHAT'S FUCKING THAT???? OH WHAT I'M FUCKING ANNIHILATING YOUR FUCKING ASS ON WITH STARFALL???????

*clears throat*

Maybe for the sake of balance, gameplay sake, it's for the best Vergil doesn't have air hike.

....but imagine in a hypothetical dmc 6 he did though.

#devil may cry#vergil sparda#dante sparda#devil may cry 5#devil may cry headcanons#non request related

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Music History (Part 1): Ancient Greece

Many ancient cultures believed that music had magic powers – that it could heal sickness, purify the body & mind, and work miracles. In the Old Testament of the Bible, David cures Saul's madness by playing the harp (1 Samuel 16:14-23); shouting and trumpet-blasts bring down the walls of Jericho (Joshua 6:12-20). In the Greek Dark Age (c.1100-800 BC), bards sang long poems in praise of heroes.

The Greeks believed music to have been invented by gods & demigods, who were also the earliest musicians – for example Apollo, Amphion (twin brother of Zethus) and Orpheus. Music was an essential part of religious ceremonies.

The main instrument for the cult of Apollo was the lyre; for the cult of Dionysus it was the aulos. Both of these instruments probably came from Asia Minor. The lyre and kithara (a bigger lyre) had 5-7 strings, and this later increased to 11. They were played solo, and to accompany epic poems (which could be sung or recited).

The aulos is sometimes incorrected translated as “flute”. It was a single-reeded instrument (sometimes double-reeded), with twin pipes. Its usage in the worship of Dionysus was to accompany the singing of dithyrambs, poems which were the predecessors of the Greek drama. In the classical age, the great tragedies of writers such as Aeschylus, Euripides and Sophocles had choruses (and other musical sections) that were accompanied by the aulos, or had alternating singing/aulos sections.

Psalteria were string instruments that were plucked with the hand, as opposed to with a plectrum. (The lyre & kithara used plectrums.) There was also a wide variety of percussion instruments.

The lyre and aulos were played independently as solo instruments from the 500's BC onwards (or perhaps earlier). Sakadas of Argos won a musical competition at the Pythian Games in 582 BC. He played Nomos Pythicos, an aulos composition that portrayed the battle between Apollo and the serpent Python.

After the 400's BC, kithara and aulos competitions became more & more popular, and so did festivals of instrumental and vocal music. As instrumental music became more independent, the number of virtuosi increased, and thus the music became more & more complex and show-offy.

Audiences of thousands would gather whenever famous musicians appeared. Kitharodes (singers who accompanied themselves on the kithara) gave concert tours and got very rich from them, especially after they'd become famous from winning competitions.

There were also famous women musicians – they were banned from competing in the games, but special decrees were written to allow the best to perform outside of the contests. However, they could only play string instruments, as the aulos was considered to be suitable only for slaves, courtesans and entertainers.

Sons of elite citizens were taught to play the aulos or kithara, and some of them aimed to reach the level of a virtuoso. (In Roman times, Nero managed this.) But Aristotle didn't approve of this, believing that music education shouldn't focus on show and flash:

The right measure will be attained if students of music stop short of the arts which are practised in professional contests, and do not seek to acquire those fantastic marvels of execution which are now the fashion in such contests, and from these have passed into education. Let the young practise even such music as we have prescribed, only until they are able to feel delight in noble melodies and rhythms, and not merely in that common part of music in which every slave or child and even some animals find pleasure.

Little survives of Greek music – about 45 pieces & fragments, from about the 200's BC – 300's AD. Some of them were written during the period of Roman dominance, but with Greek texts. All used a system of Greek notation. The most well-known are:

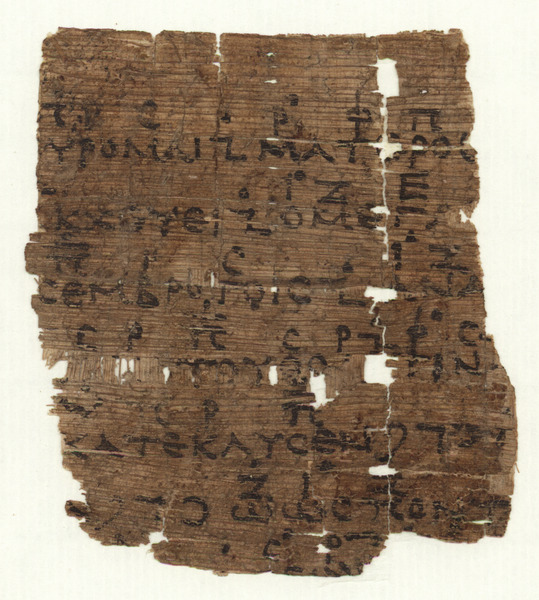

Euripides' Orestes – fragment of a chorus (lines 338-344), from a papyrus c.200 BC. The music may have been written by Euripides.

Euripides' Iphigenia in Aulis (lines 783-793).

Two Delphic hymns to Apollo, which are mostly complete. The second one is from 128-127 BC.

Epitaph of Seikilos – a tombstone epigraph probably from the 00's AD.

Hymn to Nemesis, Hymn to the Sun, and Hymn to the Muse Calliope, written by Mesomedes of Crete (100's AD).

Orestes fragment.

youtube

From these pieces & fragments, and from Greek writings on music, we know that it was mostly monophonic. Some was heterophonic – with instruments playing the melody along with a singer/ensemble, and embellishing it.

Greek music was not polyphonic. The melody & rhythm of music was tied up with that of poetry. There is no evidence that Greek music practice was continued by the early Christians.

Greek Theory

The legendary founder of Greek music theory was Pythagoras (c.500 BC), and its last important writer was Aristides Quintilianus (300's AD). Greek writings on music can be divided into two categories: a) about the nature of music, its place in the cosmos, its effects, and its place in human society (i.e. philosophy); and b) descriptions of musical composition. Western music in the medieval era was greatly influenced by Greek musical theory.

For the Greeks, the word music had a much wider meaning, being tied up with maths, poetry, and astronomy (sometimes). Music and maths were intertwined and inseparable, and it was believed that numbers were the key to the entire universe (both in the physical & spiritual sense). Therefore, music corresponded to the harmony of the cosmos, and was a microcosm of it.

Plato explained this belief in Timaeus, which was the most well-known of his dialogues during the Middle Ages, and also in his Republic. His views on the nature & uses of music affected medieval & Renaissance ideas about music, and its place in education.

Some Greek philosophers saw music as being connected with astronomy as well. Claudius Ptolemy (100's AD) was the most systematic music theorist of antiquity, and he was also the leading astronomer of those times. People like him believed that mathematic laws ordered both the celestial bodies and music intervals. Certain modes (and certain notes) corresponded with certain planets, the distances between them, and their movements.

Plato wrote about the “music of the spheres” in the Republic. This was the (inaudible) music that the planets' revolution produced. This idea was taken up by people writing about music in the Middle Ages and later (including Shakespeare & Milton).

The Greeks saw music & poetry as almost the same thing. Plato defined melos (song) as a mixture of speech, rhythm and harmony. Lyric poetry was poetry that was sung to the accompaniment of the lyre (hence the term “lyrics”). The Greek word for “tragedy” has the word ōdē (“the art of singing”) in it. Many of the Greek words for different kinds of poetry were musical terms, such as hymn.

Aristotle's Poetics states that language, melody and rhythm are the elements of poetry, and that “There is another art which imitates by means of language alone, and that either in prose or verse...but this has hitherto been without a name.” I.e., there was spoken poetry, with no music involved, but there was no word for it.

The Doctrine of Ethos

Greek writers believed that music had moral qualities (although they disagreed on which ones worked in which ways), and that it could influence or change a person's character or behaviour. This worked with the Pythagorean belief that music's pitch & rhythm was governed by those same mathematical laws that governed the physical & spiritual world. Numerical relationships kept the soul in harmony. Therefore, because music followed this numerical system, and could penetrate the soul, it could change a person, whether for better or for worse.

The belief that the legendary musicians of mythology could perform miracles was related to this, as well.

Aristotle wrote about how music could influence a person's behaviour. Music imitated the passions or states of the soul, he wrote, and a piece of music that imitated courage (for example) could make a person feel courageous. But listening to music that aroused the wrong kinds of passions (such as indolence) would distort a person's character in the long run (and vice versa).

Both Plato and Aristotle believed that a person's character could be molded the right way through a system of public education, with gymnastics to discipline the body, and music to discipline the mind.

In his Republic (c.380), Plato wrote that too much music would make a man effeminate or neurotic, but too much gymnastics would make him ignorant, uncivilized, and violent. “He who mingles music with gymnastics in the fairest proportions, and best accommodates them to the soul, may be rightly called the true musician.”

Plato was quite strict on what sort of music was suitable to listen to. Men who were being trained to govern shouldn't listen to melodies that expressed softness or indolence. In fact, they should only listen to music in Dorian and Phrygian modes, because they expressed temperance and courage. Other modes were not appropriate.

He criticized the current style of music, which used many notes & complex scales, and mixed incompatible genres, rhythms and instruments. Musical conventions should be stuck to once established, he believed, because lawlessness in art & education would lead to the same thing in society.

The saying “Let me make the songs of a nation and I care not who makes its laws” was a pun on the Greek word nomos, which meant “custom/law” and also the melodic scheme of a piece of music.

Aristotle wasn't as strict as Plato when it came to suitable modes & rhythms, and he wrote about that in his Politics (c.330 BC). He believed that music could be listened to for enjoyment as well as education. Also, he believed that emotions such as pity & fear could be “purged” by using music & drama to induce them in people.

#book: a history of western music#music#music history#history#classics#philosophy#ancient greece#ancient greek music#greek mythology#sakados of argos#nero#aristotle#euripides#mesomedes of crete#pythagoras#aristides quintilianus#plato#claudius ptolemy#lyre#aulos#kithara#music of the spheres#greek modes

6 notes

·

View notes